AdobeStock/MarLein & University of Luxembourg R

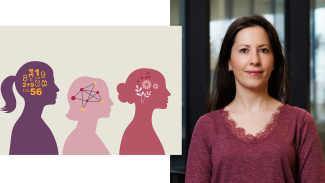

Right: Dr. Andreia Costa

Psychologist Dr. Andreia Costa researches at the University of Luxembourg how autism plays out in everyday life—with a special focus on women. In this interview, she explains what camouflaging means in this context, why masking may help in the short term but harms in the long run, how diagnostic practice has changed, and what Luxembourg is doing to help autistic people lead good lives.

Dr. Andreia Costa also advised the science.lu team for our latest “Ziel mir keng” video on the topic of autism.

Dr. Costa, what are you working on right now—and why focus on women on the autism spectrum?

I study how autistic people fare across life domains: how they regulate emotions, manage school, and navigate the transition into work—and remain there. At the moment I’m examining the role of camouflaging: strategies that make people on the spectrum appear “less autistic”. That can help with getting a job, but it makes it harder to keep one — maintaining the mask is extremely draining.

For autistic women this is particularly burdensome, because they mask more often than men. As a result, many receive a diagnosis late—or not at all—and miss out on understanding and support.

What exactly is camouflaging—and why is it so taxing?

Camouflaging means suppressing behaviors that actually help manage one’s autistic traits. For some, that means holding back self-stimulating movements; for others, forcing eye contact even when it is exhausting. Many imitate social signals to fit in. Women on the spectrum often practice eye contact, small talk, and even facial expressions—sometimes in front of a mirror.

In the short term, this opens doors. In the long term, it costs authenticity and energy. Many autistic people who camouflage say they feel “not themselves.” The consequences frequently include anxiety and depression—up to suicidal thoughts.

Why is autism in girls and women so often missed?

Several factors interact. First, difficulties often present internally: instead of outwardly noticeable behavior, you see anxiety or withdrawal—less visible to others. Second, certain intense interests are more socially accepted for girls; a girl highly interested in horses attracts less attention than a boy who talks only about locomotives. Teachers and parents often don’t think of autism. Third, social pressure plays a role: “Be polite, smile, don’t fidget.” Girls hear this more. They learn early to meet expectations and mirror other people’s behavior. All this makes diagnosis harder—and explains why the apparent gap between men and women shrinks once you look closely.

How has diagnosis changed—and why are case numbers rising?

Two things matter: awareness and criteria. Today, parents, physicians, and teachers know better what to look for to identify autistic children, support a correct diagnosis, and put the right help in place.

And since 2013 the DSM-5—American Psychiatric Association’s diagnostic manual—merged the earlier subtypes into a single spectrum; the WHO’s ICD-11 follows suit. That helps recognize diverse presentations—including people without intellectual disability and especially women.

Methodological differences also explain why U.S. figures are often higher than European ones: the U.S. screens more systematically; Europe often relies on older, heterogeneous datasets.

Why “autism spectrum”?

Spectrum means a range, not a simple ladder from “mild” to “severe.” Autistic people show different patterns of strengths and challenges that can change across the lifespan. The term “autism spectrum” makes these patterns visible so that support can be tailored—without reducing the person to a label.

DSM-5 / DSM-5-TR (USA)

Since 2013 (updated 2022), the DSM groups the former five subtypes (incl. “Asperger syndrome”) under Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Instead of boxes, it specifies severity/levels of support across two domains: social communication/interaction and restricted, repetitive behaviors (including sensory features).

ICD-11 (WHO, international/EU)

The current WHO classification follows the same principle: one spectrum instead of separate types. Again, functional impact and support needs are central. In Europe, ICD underpins billing and statistics.

How does diagnosis work in Luxembourg?

The key point of contact is the Fondation Autisme Luxembourg; the Kannerklinik at CHL also diagnoses. Teams combine behavioral observation, structured parent interviews, and cognitive and everyday-skills assessments. Interdisciplinary teams observe the child in multiple settings, and for adults, explore their history of development and difficulties; a psychiatrist validates the diagnosis at the end. Importantly, there is no simple test—the overall picture counts.

You mentioned school, university, work. Where does the transition to employment falter?

Many autistic people—especially women—can more easily secure a position by camouflaging, but then lose it because masking is unsustainable. Employers see the output, not the effort behind it. We’re developing practical guidelines: low-sensory work environments, clear routines, planned breaks, reliable communication, and genuine choice about social activities: No one should be obliged to join group lunches. People who can work without a mask last longer and are more likely to play to their strengths.

What about families—what helps parents?

Parents are often under pressure. Our studies show that well-being depends less on the diagnosis itself than on how parents appraise situations and which coping strategies they use. Those who have social support and can reframe stressful events stabilize—and indirectly help their child. Services should therefore include parents, not offer therapy for the child alone.

Terminology: “autism spectrum” or simply “autism”?

Formally, diagnostic systems use Autism Spectrum Disorder. In practice, “autism spectrum” is common to reflect diversity. Many prefer “autistic people” or “person with autism,” which feels less pathologizing. In publications, I state the classification and then use person-centered language. It’s about precision—and respect.

What do you want from society and institutions?

Fewer barriers, more self-determination. If we reduce sensory overload, clarify expectations, and offer alternatives to the “social duty mask,” everyone benefits: autistic people and their families conserve energy and employers keep their talent. Society is beginning to understand this—we’re moving in the right direction.

And what’s next for your research?

We’re launching a project to test whether learning to program can foster socio-emotional skills. We’re also continuing our work on camouflaging at the workplace—with concrete recommendations for companies in Luxembourg. In the future, we would like to continue to explore the learning opportunities given to autistic students, especially in the higher education and how this can help them navigate into successful employment.

We have also launched last October a university certificate on “

What causes autism?

Autism has no single cause. Research and clinical practice point to an interplay of many genetic and neurobiological factors that act early in brain development. Maturation and connectivity of neural circuits follow slightly different paths in some areas, so networks for social perception and sensory processing cooperate differently. This helps explain why sounds, light, or touch can feel overwhelming, while details and patterns often stand out. The range stretches from high support needs to fully independent lives—what matters is appropriate support, not the label (Wolfers et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2023).

Twin and family studies indicate a substantial hereditary component: hundreds of genetic variants each contribute a small effect, especially those involved in synapses, signal transmission, and network formation. There is no single “autism gene.” Simple external “triggers” lack evidence; large analyses find no link between vaccines and autism. As Andreia Costa stresses, we should not turn complex probabilities into blame: autism arises through many pathways, not a preventable one-off event. Effective support lowers barriers rather than moralizing about causes (Taylor et al., 2014; Wolfers et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2023).

Auteur: Hannes Schlender (scienceRELATIONS)

Éditeur: Jean-Paul Bertemes (FNR)

Infobox

Luke E. Taylor, Amy L. Swerdfeger, Guy D. Eslick, Vaccines are not associated with autism: An evidence-based meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies, Vaccine, Volume 32, Issue 29, 2014, Pages 3623-3629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.04.085

Wang L, Wang B, Wu C, Wang J, Sun M. Autism Spectrum Disorder: Neurodevelopmental Risk Factors, Biological Mechanism, and Precision Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Jan 17;24(3):1819. doi: 10.3390/ijms24031819. PMID: 36768153; PMCID: PMC9915249.

Wolfers, T. et al., From pattern classification to stratification: towards conceptualizing the heterogeneity of Autism Spectrum Disorder, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, Volume 104, 2019, Pages 240-254, ISSN 0149-7634, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.07.010.